History of the bicycle

History of the bicycle

Vehicles for human vehicles that have two haggles adjusting by the rider go back to the mid-nineteenth century. The primary method for transport utilizing two wheels organized successively, and in this way the paradigm of the bike was the german draisine going back to 1817. The term bike was instituted in France during the 1860s, and the enlightening title "penny-farthing", used to depict a "Common Bicycle", is a nineteenth-century term.

Earliest unverified bicycle

A stone cutting of an individual driving a bike can be found on the eastern side of the Gandhimathi Amman Shrine, at Panchavarnaswamy Temple Uraiyur, the Temple goes back to the seventh century AD, in spite of the fact that the cutting was likely included mid-twentieth-century renovations.[1][failed verification]

Imitation made 1965–72 from the supposed 1493 Caprotti sketch.

There are a few early, yet unconfirmed cases for the innovation of the bike.

A sketch from around 1500 AD is credited to Gian Giacomo Caprotti, an understudy of Leonardo da Vinci, yet it was portrayed by Hans-Erhard Lessing in 1998 as a deliberate fraud.[2][3] However, the genuineness of the bike sketch is still energetically kept up by supporters of Prof. Augusto Marinoni, a word specialist, and philologist, who was endowed by the Commissione Vinciana of Rome with the translation of Leonardo's Codex Atlanticus.[4][5]

Afterward, and similarly unsubstantiated, is the dispute that a specific "Comte de Sivrac" built up a célérifère in 1792, exhibiting it at the Palais-Royal in France. The célérifère as far as anyone knows had two wheels set on an inflexible wooden casing and no guiding, directional control being restricted to that achievable by leaning.[6] A rider was said to have sat with on leg on each side of the machine and pushed it along utilizing interchange feet. It is presently felt that the two-wheeled célérifère never existed (however there were four-wheelers) and it was rather a confusion by the notable French writer Louis Baudry de Saunier in 1891

19th century

1817 to 1819: the draisine or velocipede

Wooden draisine (around 1820), the most punctual bike

Drais' 1817 plan made to gauge

The main undeniable case for a for all intents and purposes utilized bike has a place with German Baron Karl von Drais, a government worker to the Grand Duke of Baden in Germany. Drais imagined his Laufmaschine (German for "running machine") in 1817, which was called Draisine (English) or Parisienne (French) by the press. Karl von Drais protected this structure in 1818, which was the primary economically fruitful two-wheeled, steerable, human-impelled machine, regularly called a velocipede, and nicknamed interest pony or dandy horse.[9] It was first fabricated in Germany and France.

Hans-Erhard Lessing (Drais' biographer) found from incidental proof that Drais' enthusiasm for finding an option in contrast to the pony was the starvation and demise of ponies brought about by crop disappointment in 1816, the Year Without a Summer (following the volcanic ejection of Tambora in 1815).[10]

On his previously revealed ride from Mannheim on June 12, 1817, he secured 13 km (eight miles) in under an hour.[11] Constructed on the whole of wood, the draisine gauged 22 kg (48 pounds), had metal bushings inside the wheel heading, iron-shod wheels, a back wheel brake and 152 mm (6 inches) of the trail of the front-wheel for a self-focusing caster impact. This structure was invited by precisely disapproved of men setting out to adjust, and a few thousand duplicates were fabricated and utilized, essentially in Western Europe and in North America. Its prevalence quickly blurred when, incompletely because of expanding quantities of mishaps, some city specialists started to disallow its utilization. In any case, in 1866 Paris a Chinese guest named Bin Chun could in any case watch foot-pushed velocipedes.[12]

On his previously revealed ride from Mannheim on June 12, 1817, he secured 13 km (eight miles) in under an hour.[11] Constructed on the whole of wood, the draisine gauged 22 kg (48 pounds), had metal bushings inside the wheel heading, iron-shod wheels, a back wheel brake and 152 mm (6 inches) of the trail of the front-wheel for a self-focusing caster impact. This structure was invited by precisely disapproved of men setting out to adjust, and a few thousand duplicates were fabricated and utilized, essentially in Western Europe and in North America. Its prevalence quickly blurred when, incompletely because of expanding quantities of mishaps, some city specialists started to disallow its utilization. In any case, in 1866 Paris a Chinese guest named Bin Chun could in any case watch foot-pushed velocipedes.[12]

Denis Johnson's child riding a velocipede, Lithograph 1819.

The idea was gotten by various British cartwrights; the most prominent was Denis Johnson of London reporting in late 1818 that he would sell an improved model.[13] New names were presented when Johnson protected his machine "passerby curricle" or "velocipede," however the openly favored monikers like "pastime horse," after the youngsters' toy or, more awful still, "dandy horse," after the dapper men who regularly rode them.[9] Johnson's machine was an enhancement for Drais's, by and large strikingly progressively exquisite: his wooden casing had a serpentine shape rather than Drais' straight one, permitting the utilization of bigger wheels without raising the rider's seat.

Throughout the late spring of 1819, the "diversion horse", thanks partially to Johnson's advertising abilities and better patent insurance, turned into the fever and style in London society. The dandies, the Corinthians of the Regency, received it, and along these lines, the writer John Keats alluded to it as "the nothing" of the day. Riders destroyed their boots shockingly quickly, and the design finished inside the year after riders on asphalts (walkways) were fined two pounds.

In any case, Drais' velocipede gave the premise to advance improvements: indeed, it was a draisine which motivated a French metalworker around 1863 to add revolving wrenches and pedals to the front-wheel center, to make the primary pedal-worked "bike" as we today comprehend the word.

In any case, Drais' velocipede gave the premise to advance improvements: indeed, it was a draisine which motivated a French metalworker around 1863 to add revolving wrenches and pedals to the front-wheel center, to make the primary pedal-worked "bike" as we today comprehend the word.

The 1820s to 1850s: a time of 3 and 4-wheelers

A couple situated on an 1886 Coventry Rotary Quadracycle for two.

McCall's first (top) and improved velocipede of 1869 – later originated before to 1839 and credited to MacMillan

In spite of the fact that actually not part of two-wheel ("bike") history, the mediating many years of the 1820s–1850s saw numerous improvements concerning human-controlled vehicles regularly utilizing advancements like the draisine, regardless of whether the possibility of a functional two-wheel configuration, requiring the rider to adjust, had been rejected. These new machines had three wheels (tricycles) or four (quadricycles) and arrived in a wide assortment of plans, utilizing pedals, treadles, and hand-wrenches, yet these structures frequently experienced high weight and high moving obstruction. Be that as it may, Willard Sawyer in Dover effectively made a scope of treadle-worked 4-wheel vehicles and sent out them worldwide in the 1850s.[13]

The 1830s: the detailed Scottish innovations

The primary precisely impelled two-wheel vehicle is accepted by some to have been worked by Kirkpatrick Macmillan, a Scottish metal forger, in 1839. A nephew later asserted that his uncle built up a back wheel drive configuration utilizing mid-mounted treadles associated by bars to a back wrench, like the transmission of a steam train. Advocates partner him with the primarily recorded occurrence of a bicycling traffic offense when a Glasgow paper revealed in 1842 a mishap in which a mysterious "man of honor from Dumfries-shire... straddle a velocipede... of shrewd structure" thumped over a walker in the Gorbals and was fined five British shillings. In any case, the proof associating this with Macmillan is frail, since it is far-fetched that the craftsman Macmillan would have been named a courteous fellow, nor is the report clear on what number of wheels the vehicle had. The proof is indistinct and may have been faked by his child.

A comparable machine was said to have been created by Gavin Dalzell of Lesmahagow, around 1845. There is no record of Dalzell ever having made a case for creating the machine. It is accepted that he replicated the thought having perceived the possibility to assist him with his neighborhood drapery business and there is some proof that he utilized the contraption to bring his products into the country network around his home. A reproduction despite everything exists today in the Glasgow Museum of Transport. The show holds the respect of being the most established bicycle in presence today.[13] The main reported maker of pole driven bikes, treadle bikes, was Thomas McCall, of Kilmarnock in 1869. The structure was propelled by the French front-wrench velocipede of the Lallement/Michaux type.[13]

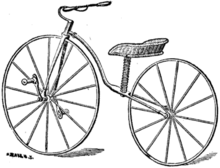

The 1860s and the Michaux "Velocipede," otherwise known as "Boneshaker"

The first extremely well known and financially effective structure was French. A model is at the Museum of Science and Technology, Ottawa.[14] Initially created around 1863, it started a chic rage quickly during 1868–70. Its plan was less complex than the Macmillan bike; it utilized turning wrenches and pedals mounted to the front wheel center point. Accelerating made it simpler for riders to push the machine at speed, yet the rotational speed restriction of this structure made soundness and solace concerns which would prompt the huge front wheel of the "penny-farthing". It was hard to pedal the wheel that was utilized for directing. The utilization of metal casings diminished the weight and gave sleeker, progressively exquisite structures, and furthermore permitted large scale manufacturing. Diverse braking systems were utilized relying upon the maker. In England, the velocipede earned the name of "bone-shaker" due to its unbending casing and iron-united wheels that brought about a "bone-shaking experience for riders."

The velocipede's renaissance started in Paris during the late 1860s. Its initial history is intricate and has been covered in some secret, not least in view of clashing patent cases: the sum total of what that has been expressed without a doubt is that a French metalworker connected pedals to the front wheel; at present, the soonest year bike antiquarians concur on is 1864. The character of the individual who connected wrenches is as yet an open inquiry at International Cycling History Conferences (ICHC). The cases of Ernest Michaux and of Pierre Lallement, and the lesser cases of back accelerating Alexandre Lefebvre, include their supporters inside the ICHC people group.

The first pedal-bike, with the serpentine casing, from Pierre Lallement's US Patent No. 59,915 drawing, 1866

New York organization Pickering and Davis concocted this pedal-bike for women in 1869.[15][16]

Bike student of history David V. Herlihy archives that Lallement professed to have made the pedal bike in Paris in 1863. He had seen somebody riding a draisine in 1862 at that point initially concocted the plan to add pedals to it. He recorded the most punctual and just patent for a pedal-driven bike, in the US in 1866. Lallement's patent drawing shows a machine which looks precisely like Johnson's draisine, yet with the pedals and turning wrenches connected to the front wheel center point, and a slim bit of iron over the highest point of the edge to go about like a spring supporting the seat, for a marginally increasingly agreeable ride.

By the mid-1860s, the metal forger Pierre Michaux, other than delivering parts for the carriage exchange, was creating "vélocipède à pédales" from a more minor perspective. The well off Olivier siblings Aimé and René were understudies in Paris as of now, and these smart youthful business people received the new machine. In 1865 they headed out from Paris to Avignon on a velocipede in just eight days. They perceived the potential benefit of creating and selling the new machine. Together with their companion Georges de la Bouglise, they shaped an organization with Pierre Michaux, Michaux et Cie ("Michaux and organization"), in 1868, maintaining a strategic distance from utilization of the Olivier family name and remaining in the background, in case the endeavor end up being a disappointment. This was the primary organization that mass-delivered bikes, supplanting the early wooden edge with one made of two bits of cast iron darted together—something else, the early Michaux machines look precisely like Lallement's patent drawing. Together with a repairman named Gabert in his old neighborhood of Lyon, Aimé Olivier made a corner to corner single-piece outline made of created iron which was a lot more grounded, and as the principal bike fever grabbed hold, numerous different metal forgers started framing organizations to make bikes utilizing the new plan. Velocipedes were costly, and when clients before long started to grumble about the Michaux serpentine cast-iron casings breaking, the Oliviers acknowledged by 1868 that they expected to supplant that structure with the askew one which their rivals were at that point utilizing, and the Michaux organization kept on ruling the business in I

By the mid-1860s, the metal forger Pierre Michaux, other than delivering parts for the carriage exchange, was creating "vélocipède à pédales" from a more minor perspective. The well off Olivier siblings Aimé and René were understudies in Paris as of now, and these smart youthful business people received the new machine. In 1865 they headed out from Paris to Avignon on a velocipede in just eight days. They perceived the potential benefit of creating and selling the new machine. Together with their companion Georges de la Bouglise, they shaped an organization with Pierre Michaux, Michaux et Cie ("Michaux and organization"), in 1868, maintaining a strategic distance from utilization of the Olivier family name and remaining in the background, in case the endeavor end up being a disappointment. This was the primary organization that mass-delivered bikes, supplanting the early wooden edge with one made of two bits of cast iron darted together—something else, the early Michaux machines look precisely like Lallement's patent drawing. Together with a repairman named Gabert in his old neighborhood of Lyon, Aimé Olivier made a corner to corner single-piece outline made of created iron which was a lot more grounded, and as the principal bike fever grabbed hold, numerous different metal forgers started framing organizations to make bikes utilizing the new plan. Velocipedes were costly, and when clients before long started to grumble about the Michaux serpentine cast-iron casings breaking, the Oliviers acknowledged by 1868 that they expected to supplant that structure with the askew one which their rivals were at that point utilizing, and the Michaux organization kept on ruling the business in I

No comments: